profile \ 05

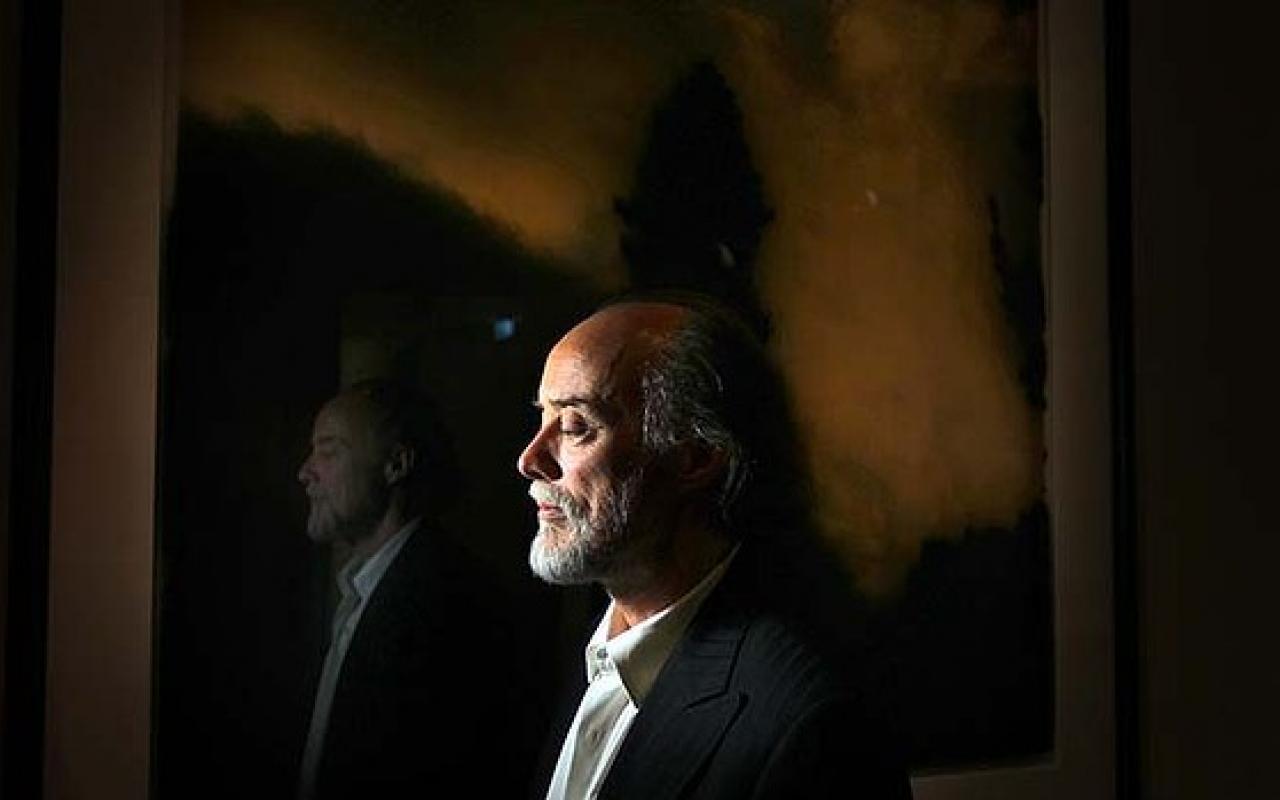

Tony Buck

Composer, Musician, Artist

Terse, twisted, ferocious, luminous and exquisite are only some of the words used to describe the music that Tony Buck creates.

Tony Buck is a prolific force and his creative vision can be traced throughout a music career that spans over three decades.

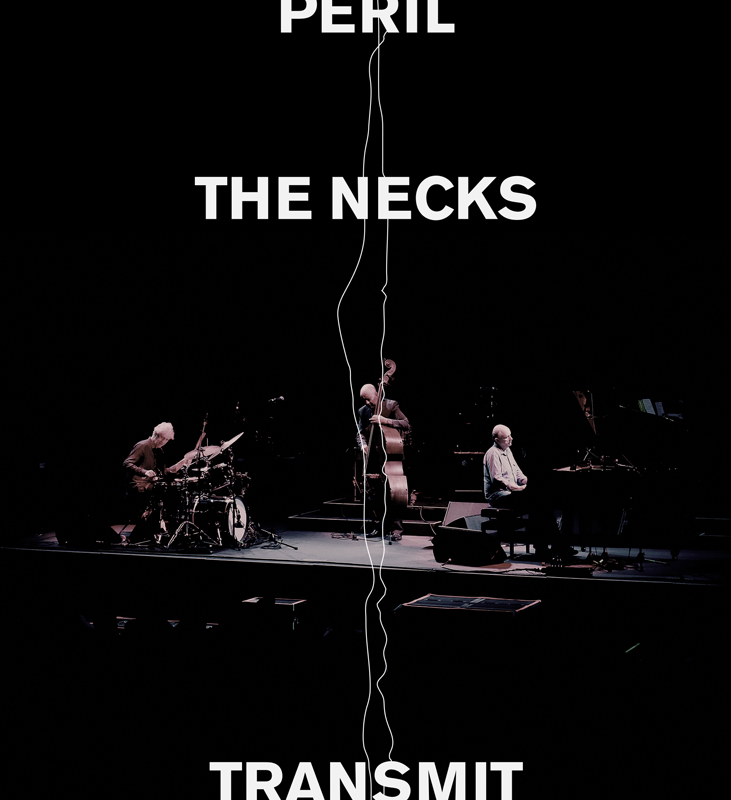

Tony is the man behind the early-to-mid-nineties Japanese/Australian industrial band Peril, the current Berlin-based group Transmit, and the New York collective Glacial, in which he has collaborated with like-minded artists Lee Ranaldo (co-founder of Sonic Youth) and bagpipist David Watson.

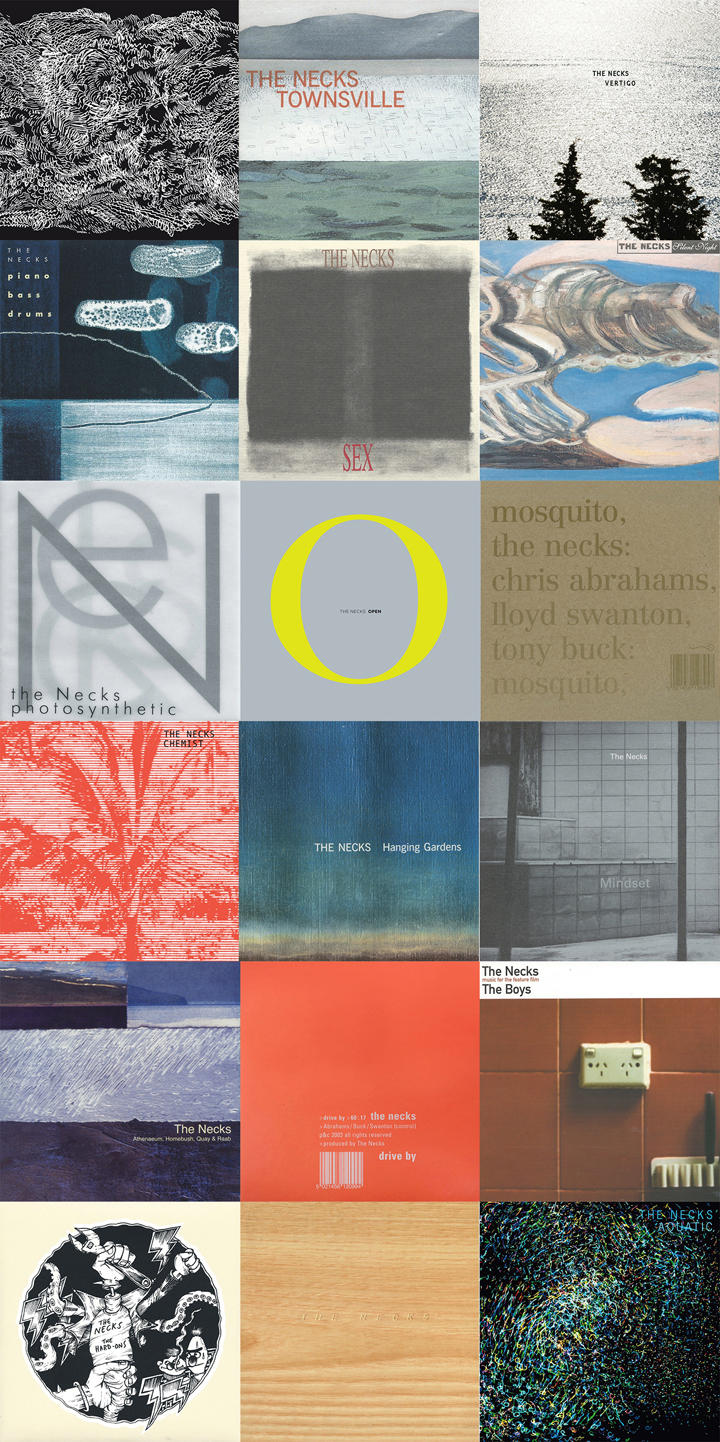

An experimentalist and improviser, Tony seeks to push against even the most peripheral boundaries of music. Evidence of this can be seen through the sound of the self-managed transcendental trio The Necks, of which Tony is a founding member alongside Chris Abrahams and Lloyd Swanton.

The Necks have been heralded as “One of the greatest bands in the world” by The New York Times and “One of the most extraordinary groups on the planet.” by The Guardian. The Necks’ music, like Tony, defies definition.

On closer inspection it seems to be in the 'in-between', and where a 'blurring of the lines' occurs, that draws Tony's attention and inspires his work.

Essentially a musician possessing and exercising an extensive repertoire; drummer, percussionist, guitarist, singer and composer, it is Tony Buck's unwavering pursuit towards a musical dialogue that challenges the ideas of perception and belief; boundaries and structure, that we at IRIS find sublime.

THE MAN IN BLACK

Text by: Glenn Wright

I first met Tony Buck at a gig at The Basement in Sydney, back in the mid '80’s. Tony would have been around 20 and I was maybe 16, trying hard to look 18 to get past the bouncer. Tony was perfectly groomed in head-to-toe black, most notably his tight, black-leather pants. He was as white as a ghost; had long, black hair, and I’m pretty sure he wore make-up. He looked more like a pop star than a jazz musician. He had a presence. His girlfriend dressed pretty much the same, and together, it was hard to take your eyes off them: they made a startling contrast to the poorly dressed and totally fashion-void conservative jazz musicians of the time.

Similarly to the visual differences, Tony’s musical differences were stark. Although he managed to play within the big-band jazz idiom, he clearly had much more going on. He was edgy, and everybody in the packed gig felt it. He was louder at times than he should be and possibly pushed the tempo a bit more than he should of, but the band didn’t seem to mind. In fact, they seemed to love it, and so did the crowd. John Hoffman, the band’s leader, kept on giving him praise and solos. I instantly became a fan and checked out the local guides for upcoming Buck gigs.

A few years later in 1986, my brother Scott and I opened a venue in Sydney just around the corner from The Basement. I became the music booker and did this for the next 16 years of my life. Scott was older and far cooler than I was, mixing with the ‘in’ crowd. His friends were young actors, soon to be movie stars. Scott’s world was possibly more about girls and the social scene than mine. He was a guy around town; I was more a music tragic. Looking back on it, however, my brother and I had a wonderful partnership. And although he was originally Scott’s friend, over time, Buck and I became great mates.

As my musical tastes were rather varied, we presented a diverse range of musical acts seven days a week, often with three or four bands a night. It wasn’t long before Tony became a regular performer in various bands. Interestingly, he no longer seemed perfectly groomed. He still looked different to the conservative jazz guys, but maybe less intimidating, less edgy. Not so much the tight-leather pants anymore, but rather suit pants (never pressed). He still wore black, but now he looked more like an artist or an inner-city musician than a pop star. His girlfriends (and there were many) also shared his inner-city look. They were always beautiful, and Tony was always 'in love.'

This hasn’t changed, actually. I mention the attire and his style because to me Tony had quickly shaken off any pretense and was now what I believe him to truly be: an artist. Someone who does what they do because it’s almost as if it’s all they can do. I doubt very much if Tony has even contemplated doing anything else with his life other than play music.

I remember a label I was once working with had come to me concerned they couldn’t come up with a cover for their album. Tony was around at the time and I mentioned this to him. He shook his head and said something like, "Can’t be much of an original band if they can’t visualise their music." It was such a Tony Buck thing to say: he couldn’t understand how an artist could so easily separate the music from the visual.

By the late '80s, Tony was possibly one of the busiest musicians in Sydney, playing pretty much every day with two to three gigs most weekends.

I was living with him at the time in a dilapidated share house in Darlinghurst. I was working at the club, so I usually got home around 2am and, for the most part, so was Tony. Sometimes he’d have another gig to go to so I tagged along. They were really fun times, hanging out in late-night bars in Kings Cross. There was a kind of musical scene in Sydney and I think we both felt in some way that we were part of a community.

The calls for Tony were diverse. He played with various jazz ensembles: The Vince Jones Band, pop group Wa Wa Nee, Paris Green, plus jazz and funk with legendary bassist Jackie Orszaczky, amongst numerous others. Alongside his more commercial calls he performed with his own groups: The Necks, L’Beato, Peril, solo projects, and improvisational collaborations with Jon Rose, The Machine For Making Sense, Nic Collins and Ground Zero. What was so interesting about Tony was that he played all these different gigs, yet it was always very much Tony Buck, and always edgy.

This Sydney scene was fun while it lasted, but by around the mid-90s, it was coming to an end. Gigs were changing and Sydney was becoming a more expensive place to live. To me, it was pretty obvious that Tony was going to get out, and he seemed to pre-empt the cultural change in the city. The Necks had begun working in Europe and Tony had been busy in Japan with his group Peril. Being a musician, he had already travelled extensively, and in 1993 Tony moved to Amsterdam to work with the musical development organisation, STEIM to help develop interactive, virtual controllers for midi and percussion interface.

He recorded and released the album Solo Live at STEIM, along with making contact and working with Dutch improv post-punk band The Ex, recording and releasing Multiverse with his group Peril on the Hong Kong label Sound Factory. He also started appearing in more and more international music festivals. In 1996, Tony moved to Berlin. Since then he’s continued to develop a reputation and career as an original performer, collaborator, band member and band leader. In the last decade, The Necks have continued to grow in popularity internationally with recognition as a truly original group –rare for an Australian band. The Necks tour Australia yearly and attendances have never been better. They’re one of the few original groups that I know who have been able to maintain an audience for an extended period while still creating new music.

In the late '90s, I took my first holiday; I hadn’t taken a break from the club since it opened. I went to Europe for two weeks and ended up visiting my good friend Tony in Berlin. It was interesting to witness Tony and his new life there. I couldn’t help feel he had found himself a new community of artists. It was as if he rediscovered what he once had in Sydney: a lively, creative community. We traveled to a jazz festival in France and I got a feel for both where he was at creatively and a taste of his lifestyle. He seemed to be touring constantly and Berlin was the best base for him. I’m told this is still the case, and the artistic community in Berlin seems to be surviving well. It seemed to me Tony had spread his wings at the right time, finding a good place to live in for what he does.

In the time that I’ve known him, Tony has changed very little. I see him once a year when he returns to Australia to tour with The Necks. Our friendship, starting in the live-music heyday of Sydney, has endured to become much stronger than I would have imagined. For my part, a friendship is based in the admiration of someone who stays true to their original spirit and Tony has always been this. As for me, I feel like the same guy who snuck in underage into The Basement to catch his first glimpse of this young, original drummer with the hot girlfriend. To this day, Tony still plays with that same intensity and originality. And I’m still a fan.

Glenn Wright is the former nightclub proprietor of Harbourside Brasserie and Managing Director of Vitamin Records.

"We are all influenced by childhood discoveries, and everyday we use such information to negotiate our way through life. As an artist I still find it amazing just how significant some of these seemingly trivial observations or events may be and how they can directly influence the way I look at and engage with the world."

There are events and situations that stay with us forever. Some things I've recently read and thought about have brought back memories that I see hold particular significance for me as a musician and artist to this day.

I recall hours sitting in the yard of our house in suburban Sydney studying the lawn and garden. I would look at the way the neat, clearly defined border between the lawn and the soil of the garden would, upon closer and closer inspection, melt away to reveal a complex interaction of varying ratios of grass-to-earth and vice versa. It was like zooming in at different resolutions to discover not where one stopped and the other began, but where and how they merged. The area where it was both lawn and garden – almost impossible to discern at a distance – became clearer and clearer... a changing ratio of a bit more of one less of the other.

It was as much a tactile and emotional response to the world around me as it was a technical example of potential devices and systems for achieving this kind of transition between different things – colours, textures and objects – a study in pointillism and ambiguity; a method of morphing one thing seamlessly or imperceptibly into another.

Memories of this experience bring back recollections of other things that happened as a child that have either informed the way I look at what I do as a musician or indicate to me that perhaps it has always somehow been in my nature to be interested in many of the things that still concern me as an artist.

Realisations from this specific, early, influential observation of the world and aspects of this information are things I can see I use often, to this day, as a composer and improviser.

TB

CAN YOU NAME A PIVOTAL MOMENT THAT LED TO THE APPROACH YOU APPLY TO THE NECKS?

CHRIS ABRAHAMS: I can’t really think of any 'pivotal' moment that contributed to the basis of The Necks' approach, beyond the decision to form the band at a time when all three of us had the space to accommodate it in our lives.

At the time I was drawn to mesmeric music that concerned itself with longer formal structures. Forming The Necks with Tony and Lloyd gave me the opportunity to develop this.

It was the first time I’d experienced the feeling of losing myself in the music; being carried along by the music I had a part in creating, whereby the direction of the music was being determined by what I was doing, as I was doing it. It was the first time I had experienced being both performer and listener at the same moment in time. That was a pivotal moment for me.

LLOYD SWANTON: For me it was reading Music Society and Education by Christopher Small. His ideas about the importance of process over product, about being 'in the moment' would have occurred to me eventually. Maybe I was already starting to think along those lines, but his book clarified these at the right time in my life, when I was asking myself a lot of questions about whether jazz and classical music really offered me the expressive options I was seeking as an artist.

TONY BUCK: For me, like Chris, I can't really name one or two central experiences that I think led to the formation of the group except to say that my developing musical interests - outside of the situations I was finding myself in - seemed to be somewhat shared by both Chris and Lloyd. That led us to thinking of alternative ways to play together.

WHAT MUSIC HAS INFLUENCED YOU AND YOUR APPROACH TO MUSIC WITHIN THE GROUP OVER THE YEARS?

CHRIS: Influence can display itself in varied forms – both imitative and avoidant. I think that an artist can choose not to follow something that he or she truly admires. Sometimes a young person can hit upon an idea that may feel original, only to find it well-populated with practitioners from a former time. This may cause the person to abandon a particular trajectory. However I’m often drawn to the aphorism 'everything has been done, but not by everyone.'

There’s a strong influence from sixties American modern jazz (Coltrane, Davis, Sanders, Shepp) as there is from the music of Fela Kuti, Lee Perry, The Beatles, Led Zeppelin, James Brown and groups like Swans and The Magic Band. More recently I think the band has become informed by European improvisation, particularly coming out of Berlin.

LLOYD: These days it's the music I'm listening to for work and play. I'm constantly soaking up influences and thinking about how they may be applied to our approach.

In the early days, what really interested me was Steve Reich's Music for Eighteen Musicians, Shhh/Peaceful by Miles Davis, the original studio recording of My Favourite Things by John Coltrane, and classical Indian for its intimacy and close focus on the building blocks of music.

IS THERE MUSIC OR SPECIFIC ARTISTS WITHOUT WHOM THE NECKS WOULDN'T EXIST IN THE SENSE THAT, ALTHOUGH NOT A DIRECT MUSICAL INFLUENCE, IT PERHAPS, SOMEHOW INSPIRED THE IDEA OR GAVE 'PERMISSION' TO DEVELOP THE NECKS AS A PROJECT?

CHRIS: I decided to become a serious musician after hearing the music of Miles Davis and John Coltrane. I wouldn’t be part of The Necks if I hadn’t had that experience. When we started the band our wish was to simply play music together without being derivative and to avoid the be-bop type structure of head-solo-head musical performance. I believe we’ve only ever really followed our intuition. I’ve always loved the piano playing of Mal Waldron, Joseph Bonner, Cecil Taylor, Thelonious Monk and Ran Blake. Piano pieces such as Jeux d’eax (Ravel), Visions Of the Amen (Massiaen), and the Bach Partitas figured strongly in my early listening, as did The Velvet Underground, The Modern Lovers, Nico, Aretha Franklin and George Clinton.

I’m also a product of the Australian rock music industry. The 'permission' to develop The Necks owes a lot to having a band mentality; an ideology whereby it’s important to act as an autonomous, collective unit within a scene, opposed to the unit being a temporary combination of individuals pursuing their own artistic trajectories. I feel that we’ve developed the band collectively and to some extent the armour that can surround a band allows for less vulnerability on the part of the members within.

LLYOD:Definitely Brian Eno. I didn't personally listen to a lot of his music before we formed the group, but in terms of his influence in the big picture, he was a real trailblazer and opened up the world's minds to perceiving music in a way that definitely made people ready to take us on our merits. To a lesser extent Steve Reich and the minimalists, for opening up Western ears to music that for the most part is fairly static harmonically.

TONY: The three of us share similar influences and favourites. The idea that a lot of these people had their own voice was a big part of what we respected about them. In that sense, music as varied as John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Fela Kuti, Stockhausen, Cabaret Voltaire and PIL all gave me encouragement to go looking for alternatives.

WHAT IS IT THAT MAKES THE NECKS UNIQUE TO OTHER GROUPS OR THE SETTINGS YOU FIND YOURSELF IN?

LLYOD: Only in The Necks do we work with almost no reliance on any other musical elements. We operate in a way that allows each one of us to function entirely as ourselves. The result is more than the sum of the parts; it is really just a bonus.

I think the closing sentence of a review on a concert in Newcastle, Australia, put it well: "Tony, Lloyd and Chris; there are no words."

IN WHAT WAYS DO OTHER MEDIUMS OR ART FORMS INFLUENCE YOUR WORK IN THE GROUP (AESTHETICALLY, TECHNICALLY, STRUCTURALLY)?

LLYOD: I have no visual expression skills, but I’m very interested in both art and architecture. I think the structures I observe there receive some sort of expression in the choices I make when I’m 'musicing.'

CHRIS: It’s hard to say how other mediums influence my music with The Necks. One of our albums features arcane sound grabs taken from various films in order to construct a subtle and false narrative. The initial idea was Tony’s but the content of the samples came from my film collection at the time and was reflective of a period in my life when I was a student of cinema.

In terms of a visual dimension to what I do in The Necks, I think very much in terms of light and dark. I’m often inspired by the stage lights shining on my closed eyes. I’ve composed for television, radio and film and with The Necks in the studio, and I use a lot of the technology that I use for film. To a large extent different technology produces different outcomes, so to some extent there is a second-hand filmic influence at work here.

CHRIS: The music of The Necks is quite narrative. The narrative takes the form of a teleology borne through what appears to be repetition. This repetition is produced by hand, as it were - a result of the limits of our human capabilities, slowly evolving with profound changes occurring. The listener and the performer can be transported – in a way similar to discursive narrative – towards climaxes and denouncements. I liken this, in some ways, to nineteenth-century tone poetry, although the narrative is abstract and in no way representative of a verbal story.

TONY: Likewise, I have never really talked to them about this subject. I’m extremely influenced by visual art, painting in particular. I know of Chris’s fascination with film at different times of his life but wasn’t sure if he drew from this with his music. For me some of the biggest aesthetic inspirations come from tactile experiences. I think playing drums is extremely sensual from the point of view of touch.

WHEN YOU PLAY IN DIFFERENT CONTINENTS DOES YOUR APPROACH TO PLAYING CHANGE?

LLYOD: Our audiences differ from continent to continent and we probably play to that to some degree. Audiences in Australia tend to be 50/50 gender split and come from the full gamut of age groups, while in Europe and the UK they tend to be older and more male.

TONY: I feel with The Necks we’ve, ironically – as an improvised music ensemble - created a form of music in Australia and are presenting it in different parts of the world. Creating the idea for this music - the processes that go towards its creation - would be a very different thing.

DOES YOUR ATTITUDE TO THE AUDIENCE, OR PERCEIVED AUDIENCE'S VIBE IN DIFFERENT PLACES CHANGE THE WAY IN WHICH YOU PLAY?

CHRIS: We play differently depending on the environment we find ourselves in. We tend to do more open air shows in Australia - although we did play at The Big Chill in the UK a few years – and my experience is that we tend to approach those shows more aggressively than we would in a more intimate space. We also tend to play at more rock venues in Australia – with large PAs - and this has a great effect on how the band plays.

LLYOD: Generally we play to the space not the audience. If a room has certain idiosyncrasies, we’ll find them in the course of our performance and incorporate them structurally into the piece. There are some occasions, however, where the mood and size of the audience is such that there’s an excitement in the atmosphere. I can certainly feel energy coming from an audience, which can be an amazing feeling and must have some influence on our performance.

TONY: Generally I think we present music that we’re feeling and hope the audience gains something from that. We’re mindful not to shape our performances on a preconceived idea on what will go down well.

HOW DO YOU FEEL ABOUT BEING LABELLED WITH A PARTICULAR STYLE?

CHRIS: People often ask us if what we do is jazz. It’s is very telling as to how we’re perceived. I don’t think we’ll ever not be considered a jazz group. Once a reputation toward being a certain style is attached to a group, it’s pretty well impossible for the band to escape the tag. At this stage of our career, I don’t think its worth worrying too much about. Problems arise when a person comes to see us, expecting a certain thing, implied by the perceived genre in which we operate, and is very disappointed. I can’t see that there’s much that can be done here. There has been some great music made under the banner of jazz which I’m happy to be associated with.

"The clarity and trust we have amongst each other will help us find measured approaches. In lots of ways I feel we’re servants of the music and the music never lets us down."

LLYOD: There's no single word that describes what we do; in some ways I think that's one of our strongest selling points. I'm comfortable with jazz being in there, so long as other words like ambient, improvised, hypnotic, long-form, atmospheric and textural are included.

TONY: I agree with Lloyd that it’s a big influence on us and is perhaps a suggestion for where jazz might be headed. I do think the other things we draw on are far removed from this form of music, especially from the perspective of what is 'required' when playing jazz. Sometime I feel more people would be motivated to check us out if it weren't for the jazz tag.

WHAT CHALLENGES DOES THE BAND FACE THESE DAYS?

LLYOD: Just maintaining that steady standard we're at. We could doubtless be doing a lot more but I went and had children, which has limited my ability to be absolutely free to do whatever the band is offered. But I think the guys are okay with that. And anyway, everything about this band is fatalistic (except our fanatical, unswerving dedication to fatalism.)

CHRIS: I think we should never lose sight of the basic principle of the band, which is: one thing leads to another thing.

TONY: I agree with Chris, that one of the best things the band does is let one thing follow from the other. In this day and age a lot of things that were once a given no longer apply. Issues like the cost of touring and downloading leading to loss of income are all big issues: boring and over-discussed. The clarity and trust we have amongst each other will help us find measured approaches.

In lots of ways I feel we’re servants of the music and the music never lets us down...